A question that enters readers minds often when reading The Sound and The Fury is, why doesn't Caddy have her own chapter? She is arguably the most important character in the book, as she affects the fate of every other character. The story is about the downfall of the Compson family, and Caddy causes this downfall with her promiscuity, so it seems logical that she should be one of the narrators. However, she is not. This may be because, while Caddy is integral to the story, the story is not actually about her; it is instead about her affect on the rest of the Compsons, most notably her three brothers, Benjy, Quentin, and Jason. Thus, each of the three brothers have a chapter, while Caddy does not.

Also, while Caddy does cause the downfall of the Compsons, it is not unthinkable that they would still have fallen down without her help. Mr. Compson is a cynical drunk, Mrs. Compson is vain and self-centered, Benjy is mentally disabled, Quentin is obsessed with a code of honor which does not exist anymore, and Jason is just plain mean. Caddy did not give any of these characters their flaws, she only enhanced them. By the end of the book, Caddy is not really even a part of the Compson family anymore; she has "jumped ship," to use our classroom metaphor. Thus, as she is no longer a part of the the story of the Compson's downfall, she cannot be its narrator, despite the fact that she is the catalyst for the story.

Saturday, April 5, 2008

Tuesday, March 11, 2008

My Only Friend, The End

"I came upon a boiler wallowing in the grass, then found a path leading up the hill. It was turned aside for the boulders, and also for an undersized railway-truck lying there on its back with its wheels in the air, One was off. The thing looked as dead as the carcass of some animal. I came upon more pieces of decaying machinery, a stack of rusty nails." - Heart of Darkness

One of the images in Apocalypse Now that came to mind when I read this passage was that of the downed Huey helicopter lying in flames. The Huey is often considered the workhorse of the Vietnam war, and, in the beginning of the movie, the helicopter is shown most often as flying triumphantly through sky, especially with "Ride of the Valkieries" playing behind it or Playboy bunnies dancing in front of it. However, towards the end of the movie, it is only shown as hanging in a tree or lying in a ditch, its crew nowhere to be found, accompanied only by eerie techno music. It looks just as much like "the carcass of some dead animal" as the railway-truck. The technological might of the Huey is no match or the harsh realities of war.

One of the images in Apocalypse Now that came to mind when I read this passage was that of the downed Huey helicopter lying in flames. The Huey is often considered the workhorse of the Vietnam war, and, in the beginning of the movie, the helicopter is shown most often as flying triumphantly through sky, especially with "Ride of the Valkieries" playing behind it or Playboy bunnies dancing in front of it. However, towards the end of the movie, it is only shown as hanging in a tree or lying in a ditch, its crew nowhere to be found, accompanied only by eerie techno music. It looks just as much like "the carcass of some dead animal" as the railway-truck. The technological might of the Huey is no match or the harsh realities of war.

Like the Huey, the railway-truck can also be considered the workhorse of the European colonizers. It was designed to carry things great distances, and, like the Huey, it is a symbol of industrial superiority. This rotting piece of industrial might is one of the first things Marlow sees when he arrives at the first outpost, and it signifies the things to come; the Imperial "workhorse" that Marlow will try to find, Kurtz, is also rotting, if only in his soul (the same can be said of Apocalypse Now's Colonel Kurtz).

Like the Huey, the railway-truck can also be considered the workhorse of the European colonizers. It was designed to carry things great distances, and, like the Huey, it is a symbol of industrial superiority. This rotting piece of industrial might is one of the first things Marlow sees when he arrives at the first outpost, and it signifies the things to come; the Imperial "workhorse" that Marlow will try to find, Kurtz, is also rotting, if only in his soul (the same can be said of Apocalypse Now's Colonel Kurtz).

Both the Huey and the railway-truck are technological advancements that were used by a large power to assert its will over a much weaker culture. By showing both as "carcass[es]," Apocalypse Now and Heart of Darkness are alluding how such a crusade can destroy not only the oppressed, but also the oppressors, as shown by both Kurtzes.

One of the images in Apocalypse Now that came to mind when I read this passage was that of the downed Huey helicopter lying in flames. The Huey is often considered the workhorse of the Vietnam war, and, in the beginning of the movie, the helicopter is shown most often as flying triumphantly through sky, especially with "Ride of the Valkieries" playing behind it or Playboy bunnies dancing in front of it. However, towards the end of the movie, it is only shown as hanging in a tree or lying in a ditch, its crew nowhere to be found, accompanied only by eerie techno music. It looks just as much like "the carcass of some dead animal" as the railway-truck. The technological might of the Huey is no match or the harsh realities of war.

One of the images in Apocalypse Now that came to mind when I read this passage was that of the downed Huey helicopter lying in flames. The Huey is often considered the workhorse of the Vietnam war, and, in the beginning of the movie, the helicopter is shown most often as flying triumphantly through sky, especially with "Ride of the Valkieries" playing behind it or Playboy bunnies dancing in front of it. However, towards the end of the movie, it is only shown as hanging in a tree or lying in a ditch, its crew nowhere to be found, accompanied only by eerie techno music. It looks just as much like "the carcass of some dead animal" as the railway-truck. The technological might of the Huey is no match or the harsh realities of war. Like the Huey, the railway-truck can also be considered the workhorse of the European colonizers. It was designed to carry things great distances, and, like the Huey, it is a symbol of industrial superiority. This rotting piece of industrial might is one of the first things Marlow sees when he arrives at the first outpost, and it signifies the things to come; the Imperial "workhorse" that Marlow will try to find, Kurtz, is also rotting, if only in his soul (the same can be said of Apocalypse Now's Colonel Kurtz).

Like the Huey, the railway-truck can also be considered the workhorse of the European colonizers. It was designed to carry things great distances, and, like the Huey, it is a symbol of industrial superiority. This rotting piece of industrial might is one of the first things Marlow sees when he arrives at the first outpost, and it signifies the things to come; the Imperial "workhorse" that Marlow will try to find, Kurtz, is also rotting, if only in his soul (the same can be said of Apocalypse Now's Colonel Kurtz).Both the Huey and the railway-truck are technological advancements that were used by a large power to assert its will over a much weaker culture. By showing both as "carcass[es]," Apocalypse Now and Heart of Darkness are alluding how such a crusade can destroy not only the oppressed, but also the oppressors, as shown by both Kurtzes.

Tuesday, February 12, 2008

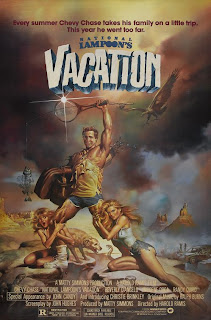

National Lampoon's Deceptively Simple Vacation

Probably the most complex of the stories we've read is A Good Man is Hard to Find, by Flannery O'Conner. The reason is almost as simple as the story first appears to be. Because nothing in the story actually happened in real life, and none of the characters are real people, we can assume that O'Conner made them all up. Also, because this story is not only in a literature textbook but also being taught in a literature class, we can also assume that it is an example of "good" writing. Therefore, everything in the story, every word, character, place, action, etc., must have a purpose or some deeper meaning, or else it would not be in there. And A Good Man is Hard to Find is chock full of things and actions that must have some sort of purpose. Also, none of these hidden meanings are obvious, and most don't seem to be there at all. This makes the story seem all the more simple, but therefore more complex. At first glance, it appears to just be a story about a family vacation gone tragically wrong, but we know it must be so much more than that, or else analyzing it would be pointless.

Perhaps the most elusive of all the meanings in the play is the Grandmother's final words: "Why you're one of my babies. You're one of my own children!" The more those lines are analyzed, the more complex they are revealed to be. The title is also deceptively simple, like the rest of the story. Were this not a "good" piece of literature, the story would probably be about someone attempting to seek out a good man, and how difficult such a venture would be. This story is nothing like that. In A Good Man is Hard to Find there are men who seem good but may also be bad, and bad men who may also be good. None are sought and none are found. Thus, the title, like the rest of the story, must be a part of the deeper meaning, or else it would not have been included. None of the other stories' meanings are so elusive.

Friday, February 8, 2008

Othello Essay - NOT The Final For Serious Draft

One of the most common elements of all the works is the lack of control the characters have over what happens to them, and how they deal with this lack of control. In A Prayer for Owen Meany and Oedipus Rex, the characters are controlled by their fate, and a higher power. In Othello, on the other hand, everything that happens to the titular character is caused by a mortal, Iago; while Iago is made more evil because of his refusal to accept things as they are, Othello reveals his nobility through his acceptance of the consequences at the end.

From the moment Iago convinces Cassio to drink at the party to when Iago confesses to all that he has done, Othello does not have control over his what he does and what happens to him. He is bound by his sense of honor and his inherent insecurities to trust Iago and lose his faith in Desdemona. In this lies Iago's genius. Like Oedipus had no choice in killing his father and marrying his mother, and how Owen had no choice in sacrificing himself for the Vietnamese kids, Othello has no choice in destroying his life. He is “as tenderly… led by the nose as asses are” (Act I, Scene III) by Iago. Shakespeare is playing with one of our greatest fears in Othello - that we have little or no control over what happens to us. The scariest part of Othello is that, unlike Owen Meany and Oedipus, Othello's fate is not controlled by a higher power, which probably has good intentions. Instead, the fate of Othello is controlled by a man, one who most definitely has very bad intentions.

Although Iago's motives are never fully revealed or explained, what he is doing is pretty straightforward: he is playing god. He is basically playing the part of the Greek gods in Oedipus and the Christian god in Owen Meany. Iago refuses to accept that Othello could choose “a great arithmetician” (Act I, Scene I) as his lieutenant instead of him, and attempts to change this fact by acting as a god. However, by acting as a god, Iago loses his humanity, and thus becomes more evil. In Oedipus and Owen Meany the higher powers are regarded as unfeeling, unknowable forces that lack human compassion but have an unquestionable sense of right and wrong. In both works, the characters have no choice in following the will of the gods, but they assume that the gods know what they are doing, and they accept it. Iago, however, is only human, but by attempting to elevate himself to the status of a god he loses his compassion but does not gain a sense of right and wrong. All he is left with is great power and great anger, and that can only mean doom for all those around him.

Because Othello is Iago's counterpart, instead of controlling others he is the one being controlled. Also unlike Iago, he is honorable and compassionate, and, when he realizes the truth about what has happened, he accepts it. He admits that he was “one who loved not wisely but too well” (Act V, Scene II). Like Oedipus at the end of his play and Owen throughout his book, accepting that he has no control over what happens to him is what makes Othello noble. Rodrigo, in sharp contrast to Othello as Iago's right-hand man, does just the opposite. Instead of accepting that he can never have Desdemona, he asks Iago, the controlling force in the play, to change his fate, which, of course, doesn’t happen. Thus Rodrigo, unlike Othello, is generally regarded as weak, dishonorable, and “a fool” (Act I, Scene III). All three works show their characters' essential nobility through whether or not they accept and take responsibility for what they do, despite the fact that they are not in control over what happens to them.

Othello, like Oedipus and Owen Meany, is noble because he has no control over his destiny and he accepts that; Iago is evil because he does not accept what happens to him and tries to play the respective parts of the Greek gods in Oedipus and the Christian god in Owen Meany. What we do when we can't control what happens to us and how we try to control what happens to others are essential parts of human nature and thus important parts of Othello, as well as Oedipus Rex and A Prayer for Owen Meany.

Friday, February 1, 2008

FATE in OTHELLO - 1st Essay Rough Draft

Fate is evident in all of the works, but almost most so in Othello. However, in Othello, fate does not mean so much the idea that your destiny is predetermined, like in Oedipus Rex or A Prayer For Owen Meany; fate in Othello is more the idea of how little control we actually have over our own destiny. In the play, Othello's fate is controlled almost entirely by Iago, who essentially plays God; Othello not having control over his fate and accepting that he has no control in the end is part of what makes him noble.

From the moment Iago convinces Cassio to drink at the party to when Iago confesses to all that he has done, Othello does not have control over his destiny. He is bound by his sense of honor and his inherent insecurities to trust Iago and lose his faith in Desdemona. In this lies Iago's genius. Like Oedipus had no choice in in killing his father and marrying his mother, and how Owen had no choice in sacrificing himselffor the Vietnamese kids, Othello has no choice in destroying his life. Shakespeare is playing with one of our greatest fears in Othello - that we have little or no control over what happens to us. The scariest part of Othello is that, unlike Owen Meany and Oedipus, Othello's fate is not controlled by a higher power, which probably has good intentions. Instead, the fate of Othello is controlled by a man, one who most definitely has very bad intentions.

Although Iago's motives are never fully revealed or explained, what he is doing is pretty straightforward: he is playing god. He is basically playing the part of the Greek gods in Oedipus and the Christian god in Owen Meany. By acting as a god, Iago loses his humanity, and thus becomes more evil. In Oedipus and Owen Meany the higher powers are regarded as unfeeling, unknowable forces that lack human compassion but have an unquestionable sense of right and wrong. In both works, the characters have no choice in following the will of the gods, because it is assumed that the gods know what they are doing. Iago, however, is nevertheless still only human, but by attempting to elevate himself to the status of a god he loses his compassion but does not gain a sense of right and wrong. All he is left with is great power and great anger, and that can only mean doom for all those around him.

Because Othello is Iago's counterpart, instead of controlling others he is the one being controlled. Also unlike Iago, he is honorable and compassionate, and, when he realizes the truthabout what has happened, he accepts it. Like Oedipus at the end of his play and Owen throughout his book, accepting that he has no control over what happens to him is what makes Othello noble. Rodrigo, in sharp contrast to Othello, does just the opposite. Instead of accepting that he can never have Desdemona, he asks Iago, the controlling force in the play, to change his fate. Thus Rodrigo, unlike Othello, is generally regarded as weak and dishonorable. All three works show their characters' essential nobility through whether or not they not only accept their fate, but also take responsibility for it nonetheless.

Othello, like Oedipus and Owen Meany, is noble because he has no control over his destiny and he accepts that; Iago is evil because he tries to play the respective parts of the Greek gods in Oedipus and the Christian god in Owen Meany. What we do when we can't control what happens to us and how we try to control what happens to others are essential parts of human nature and thus important parts of Othello, as well as Oedipus Rex and A Prayer for Owen Meany.

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

He's a maniac, maniac, on the floor. And he's setting fire to reality like he's never set fire to reality before.

"Iago, as Harold Goddard finely remarked, is always at war; he is a moral pyromaniac setting fire to all of reality.......In Iago, what was the religion of war, when he worshiped Othello as its god, has now become the game of war, to be played everywhere except upon the battlefield."

--Harold Bloom

I guess since a "pyromaniac" is someone who likes setting fire to things, then a "moral pyromaniac" is someone who likes setting fire to morality, and, apparently, "all of reality." Unfortunately, that isn't nearly as cool as it sounds. What Bloom is saying is that Iago feels a compulsion to destroy Othello, Desdemona, and Cassio's "reality," and not that Iago is a supreme being with a Satan-like pyrotechnic super-power, like I imagined when I first read the quote. Then I realized that Satan-powers would perfectly fit Iago's self-characterization of himself as a "devil," and I understood why Iago would be a moral pyromaniac instead of, say, a moral destructimaniac.

I guess since a "pyromaniac" is someone who likes setting fire to things, then a "moral pyromaniac" is someone who likes setting fire to morality, and, apparently, "all of reality." Unfortunately, that isn't nearly as cool as it sounds. What Bloom is saying is that Iago feels a compulsion to destroy Othello, Desdemona, and Cassio's "reality," and not that Iago is a supreme being with a Satan-like pyrotechnic super-power, like I imagined when I first read the quote. Then I realized that Satan-powers would perfectly fit Iago's self-characterization of himself as a "devil," and I understood why Iago would be a moral pyromaniac instead of, say, a moral destructimaniac. Because Iago was a soldier before the story begins, it makes since that, like any successful soldier, war would have been his religion, and Othello, as his commanding officer, would have been akin to his god. However, when he felt his "god" had forsaken him, Iago lost faith in his religion, and it became nothing more to him than a game. Also because of his moral pyromania, an appetite for destruction which he may have acquired on the battlefield, his only response could be all-out war. Only now, he would be fighting in the battlefield of everyday life, playing his cruel game with those who he formerly called his allies.

Because Iago was a soldier before the story begins, it makes since that, like any successful soldier, war would have been his religion, and Othello, as his commanding officer, would have been akin to his god. However, when he felt his "god" had forsaken him, Iago lost faith in his religion, and it became nothing more to him than a game. Also because of his moral pyromania, an appetite for destruction which he may have acquired on the battlefield, his only response could be all-out war. Only now, he would be fighting in the battlefield of everyday life, playing his cruel game with those who he formerly called his allies.

Friday, January 11, 2008

From Oedipus Rex, I Walked Away With...

...these things. For one, the Greek gods liked to screw with people a lot. Also, if someone says "You don't wanna know," then you probably don't wanna know. Finally, killing your father and having kids with your mother is not a good thing to do, ever.

More seriously, I didn't understand why Oedipus was made responsible for something he had no control over. It's like being punished for sneezing or waking up in the morning. I guess the Greeks had a different understanding of responsibility than we do.I also think this play is harder to fully understand in a society that values free will so much.

I think these describe me pretty well...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)